We rely more and more on electronic devices to manage our daily lives, everything from refrigerators to cell phones, automobiles to sewage plants. What if all those devices stopped working… simultaneously?

Couldn’t happen, you say?

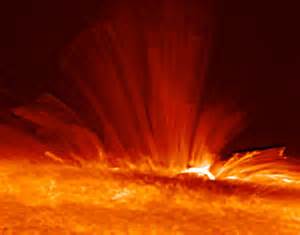

It could, actually, and almost did. July 23, 2012. An errant solar flare, launching itself into space as such things do, narrowly missed our tiny planet. Well, “narrowly” as defined in space terms. Still, had the flare occurred a mere week earlier, every electronic device on the planet would have been instantly transformed into a very expensive paperweight.

First would come X-rays and extreme UV radiation, affecting radio and satellites. Then, a day or so later, a gigantic cloud of magnetized plasma called a coronal mass ejection (CME) would disable anything electrical on the planet.

If that sounds like a doomsday scenario, be aware that it has already happened once, and in the not-so-distant past. In September 1859, English astronomer Richard Carrington observed a massive solar flare erupt from the sun’s surface. In the next few days, a series of CMEs hit the earth, creating Northern Lights as far south as Cuba and causing telegraph lines to spark and, in some cases, setting fire to the telegraph offices. Some stations even reported being able to transmit along the wires without benefit of externally-applied electricity– the CMEs were generating enough to keep the system operational.

Of course, that event occurred before modern electronics were even dreamed of. Telegraph existed, but hadn’t reached across the continent yet; viable telephones were more than a decade in the future. The solar flare was startling, but effects were minimal.

The impact would, of course, be infinitely more destructive today. The world has become dependent upon computers and sophisticated electronics.

Following the close call in July 2012, physicist Pete Riley of Predictive Science Inc. published an estimate of how frequent a solar storm as violent and destructive as the 1859 ejection might be. He calculated a 12% chance of such a storm hitting the earth within ten years.

Sobering? Perhaps, but look at it this way. If you’re reading this post, it hasn’t happened yet, and maybe it won’t. Even if it does, we’ll just have to re-run the last 160 years or so all over again. And maybe, this time, we’ll get it right.